Lee Trevino’s golf interest was waning. Then along came Ben Hogan

In the 67 years since they were published, the teachings in “Ben Hogan’s Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals of Golf” haven’t changed.

But the writing around them has.

A new edition of the landmark book has just been released (publisher Avid Reader Press hails it as “the definitive edition”), featuring never-before-seen photos and memorabilia from the Hogan estate archives.

There’s also a new introduction by Lee Trevino.

As personalities, the garrulous Trevino and the stoic Hogan could hardly be more different. But they shared defining traits as up-from-nothing Texans who got into golf through caddying and taught themselves to play by digging answers from the dirt. And that’s not where the ties between them end.

Another link is the debt Trevino says he owes to Hogan for helping put him on a path to success long before the two ever met.

It’s a story Trevino recounts in his introduction, kicking off the narrative in December 1957. By then, the 17-year-old Trevino was already showing promise in the game, but he was also restless and directionless. “I was feeling lost and beginning to get into trouble,” he writes. Seeking structure, he mothballed his sticks and joined the Marines, leaving behind his dollar-an-hour job at a driving range for 13-week bootcamp at Camp Pendleton in Southern California. After that, it was off to Yokohama.

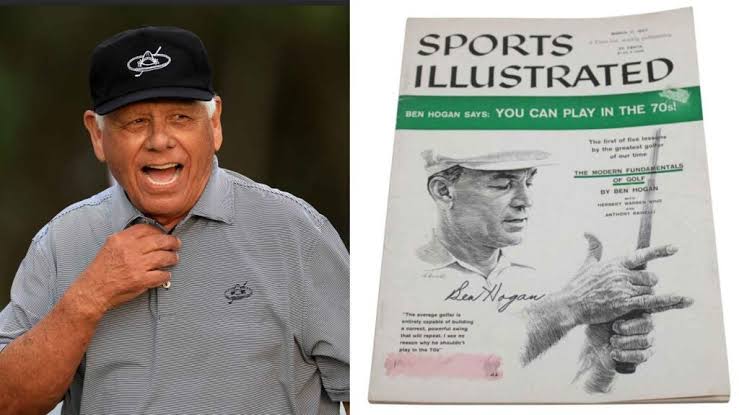

As Trevino boarded a troop ship for what would be a 22-day voyage from San Diego to Japan, “golf,” he writes, “was the furthest thing from my mind.” That changed, though, when he wandered into the ship’s library and came across a copy the March 11, 1957, issue of Sports Illustrated, which contained the first installment of a five-part instructional series by a certain famous Texan.

At the time, Trevino knew the name but little else about Hogan. But bootcamp, he writes, had “given me a crash course in structure and discipline for the first time in my life.” A few pages into the article, Trevino sensed that he’d found a kindred spirit and felt “the golf bug stirring again.”

The rest is history, with colorful side notes. Trevino would go on to join the Marines golf team, playing in his first tournaments and winning his first individual titles. A star was born.

After his discharge from the military, Trevino returned to Dallas with renewed fire and focus. When he wasn’t on the range or playing money matches, he’d light out for the course alone and play two balls, imagining that one of them was Hogan’s. In time, he would cross paths with the man himself.

Trevino relays the oft-repeated tale of going to play a round at Shady Oaks Country Club, Hogan’s home course, and seeing Hogan on the range, smashing balls toward a caddie who barely had to move to retrieve the shots. Watching from a distance, Trevino says he noticed how Hogan “controlled his shots with his lower body. And that the more he led with his hips and his legs, the more he’d fade the shot left to right.” In those days, Trevino played a draw that often betrayed him under pressure. Hogan’s method for producing a fade became another foundational lesson. “What I’m saying,” Trevino writes, “is that Hogan is the reason I developed my game.” His gratitude was so great that after winning his first major, the 1968 U.S. Open, he dedicated his own instructional book to Hogan.

The two wound up being members of a mutual admiration club. Though their primes didn’t overlap, they were paired together in the final round of the 1970 Houston Champions Invitational, when Hogan was 56. They finished side by side, in a tie for 9th. Hogan, for his part, made a special effort to watch Trevino play whenever the Colonial Invitational rolled around. According to Trevino, whenever Hogan was getting ready to release a new line of his namesake clubs, he’d give one of his reps the following instructions: “Take this set over to Dallas and let that little Mexican boy hit ‘em. He’ll tell me if they’re solid.”

“And I didn’t have any problem with that,” Trevino says.

In closing, Trevino shares one final pearl of truth he picked up from Hogan. “Whether you’re practicing or playing, school yourself to think in terms of cause and not the result.” Trevino seized on that. “I called myself an uneducated engineer who could dissect a problem, find the why and fix it,” he writes.

But the process never ends. Even in his twilight, Hogan remained a range rat. Like the man he learned so much from, Trevino is the same.

As he puts it: “I’m still trying to figure it out at age eighty-five.”