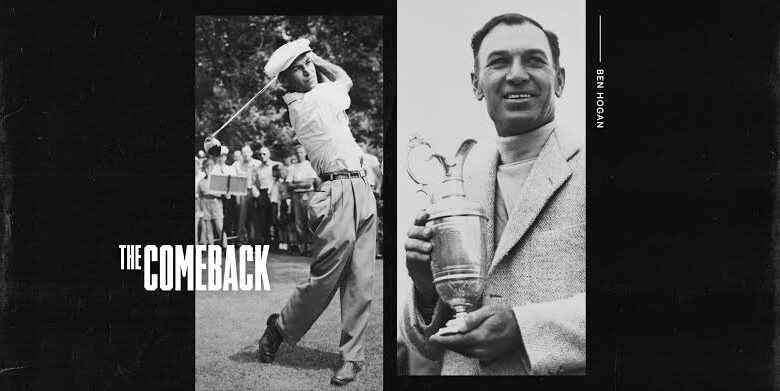

The Comeback, No. 17: Ben Hogan, from a near-fatal crash to 6 more major titles

All we see is Ben Hogan’s back. The past. That image. The 1-iron at Merion, the shot that secured an 18-hole playoff at the 1950 U.S. Open. It is golf’s version of Ali hovering over Liston, of Dwight Clark’s outstretched fingers pulling Joe Montana’s pass out of the sky. Hogan’s finish is perfection. High hands, total balance. An endless gallery looks not at him, but at a ball in flight, one sailing impossibly straight. We never see Hogan’s face. Only his silhouette — an effigy of golf’s golden age.

This is how, as it happens for men of his era, Hogan is recast as a myth for those of us who never saw him play.

The story is told that Hogan won that U.S. Open to complete the most unfathomable return in golf history. Only 16 months earlier his body had been mangled in a car crash that probably should’ve killed him. Hogan not only played again, but also won again, capturing six of his nine majors, all between the ages of 37 and 41. Dan Jenkins called it “probably the most incredible comeback in the history of sports.” Amid his own rebound, Tiger Woods said in 2018 that it is “one of the greatest comebacks there is and it happens to be in our sport.”

This is where the aura takes shape.

We’re told Hogan’s swing is one of the greatest of them all. Maybe the best ever. We’re told he grew up poor in Texas as the son of a blacksmith named Chester Hogan. Life was hard. In 1922, it got too hard. Chester killed himself with a shotgun blast to the chest, horrifying and shattering his wife, Clara, and the couple’s three kids: Princess, Royal and young Ben, who was all of 9 years old. It has been speculated over the years that Ben may have witnessed the event. The fact there is no firm answer speaks to Hogan’s steely and sometimes reclusive disposition. He was one of the faces of American sport in the postwar decade, a hero whose biopic was made into a feature film starring Glenn Ford in 1951. Yet Hogan never publicly spoke of his father’s death. Hogan’s golf career had begun two decades earlier, in 1930, when he dropped out of high school six months shy of his 18th birthday to turn pro. He didn’t win his first tournament until 1940 and didn’t win his first major until 1946. He still finished his career with 64 wins, a total that ranks as the fourth-most on the PGA Tour. We’re told of the secrecy that entwines so much of his story. Late in life, when asked for lessons, he’d confide the swing tweaks he made in the late ’40s that eliminated his hook and changed the trajectory of his career, but would tell the recipient, “You can use this tip, but don’t tell anyone where you got it.” In truth, none of Hogan’s secrets could be replicated. The man’s swing had its own DNA and he honed it by inventing the modern notion of practice. You can’t try to be Ben Hogan.

Added all up, this is where Hogan’s folk lore is born. Other than his wife, Valerie, and his brother, Royal, no one was invited inside his world. Even friends were only visitors. Byron Nelson knew Hogan since childhood. In one of golf’s all-time ties that bind, the two grew up as caddies at Glen Garden Country Club in Fort Worth, Texas. But it was Nelson who wrote in Sports Illustrated upon Hogan’s death in 1997: “The Hogan mystique will never be explained — not even by those of us who got as close to him as he would allow. He was a most unusual man.”

It is in his comeback, though, if you look hard enough, where the most human version of Ben Hogan emerges.

That’s what Charles Bartlett found in late March 1949 — a man, broken to pieces, at his most vulnerable.

Bartlett, the golf editor of the Chicago Tribune for 36 years, and for whom the press lounge at Augusta National is named, was granted an exclusive interview with Hogan at Hotel Dieu, an El Paso, Texas, hospital. It was only eight weeks removed from the crash, when the car Hogan was driving from El Paso to Fort Worth, collided head-on with a Greyhound bus. His injuries filled the chart: fractured pelvis, broken collarbone, chipped ribs and a fractured left ankle. Hogan underwent numerous surgeries and six blood transfusions.

Bartlett, who died in 1967, wrote he wasn’t sure what to expect upon seeing Hogan. The defending U.S. Open champion was only 5 feet, 8 inches, and had never weighed more than 142 pounds. When he was climbing the ranks among the best golfers in the world, Hogan was referred to in newspaper accounts as “Bantam Ben” and “Tiny Ben.” It wasn’t much of a slight because Hogan’s swing was that of a giant.

That version of Hogan was a distant memory when Bartlett arrived. He instead found “a wan, weary little man who has now spent nearly two months beating death, the roughest player of them all.”

Bartlett asked Hogan: “Will you play golf again? Not when … but will you play?”

“I’m going to try,” Hogan replied. “It’s going to be a long haul, and in my mind, I don’t think that I’ll ever get back the playing edge I had last year. You work for perfection all your life, and then something like this happens. My nervous system has been shot by this, and I don’t see how I can readjust it to competitive golf. But you can bet I’ll be back there swinging.”

Back there swinging?

It seemed like a preposterous statement, considering the magnitude of the crash he had been lucky just to survive. Ben and Valerie were driving east along Highway 80, navigating a heavy fog, around 8:30 a.m. on Feb. 2, 1949. They were in the middle of nowhere, having just passed through a West Texas ranch town called Kent. With the road slowly unfolding before them, Hogan squeezed the wheel as four headlights suddenly appeared in front of him — two from a truck approaching in the left lane, and two from a Greyhound bus trying to pass the truck in Hogan’s lane. He jerked the wheel, but was boxed in by a guard rail. In an instant, wide-eyed, Ben threw himself to his right, across Valerie. The bus motored directly through the front of the Hogans’ 1949 Cadillac, sending it backwards down the highway.

Ben blacked out immediately. Valerie was dazed, but conscious. The car dashboard sandwiched into them. The Associated Press reported the car’s steering wheel had “jammed back into the driver’s seat.” If Hogan hadn’t hurled himself to save his wife, he’d have surely been crushed to death.

Chaos ensued. A truck trailing the accident jackknifed, triggering a pileup. Valerie lowered the passenger-side window and yelled for help. She pushed the door open and squeezed herself out. Finally, two passersby arrived and helped her pull a dazed Ben from the car. His clubs were in the backseat.

Ben and Valerie drove to California for the Oakland Open. It was the end of the road, unless something changed. Before the first round, the tires were stolen off the Hogans’ Buick and he arrived late for the first round. He played without taking a practice swing.

Three days later, Hogan finished third and won $385. It was a pivot point in history.

Hogan went on to land in the money in 56 consecutive tournaments, including his first win, the 1940 North and South Open at Pinehurst, a victory that came nine years after he had turned professional. Hogan was the tour’s leading money winner in 1940, ’41 and ’42, winning 15 times in that stretch. After spending 1943, ’44 and most of ’45 in the service, he returned to the tour and captured his first major in 1946 (the PGA Championship) at age 34 and added two more in 1948 (PGA, U.S. Open).

Heading into the 1950 season, it was widely thought Hogan might attempt to return for the Masters, even if only ceremonially. Word soon spread, though, that he was on his way to Riviera Country Club to compete in the season-opening Los Angeles Open — an event slated for Jan. 6, 1950, just 11 months removed from the crash. It was reported that Hogan had resumed playing six weeks earlier and arrived in L.A. having only completed a handful of 18-hole rounds. No one was quite sure what they were seeing when he showed up at Riviera for a series of practice rounds. He fired scores of 70, 67, 76 and 67.

At a luncheon prior to the tournament, Cary Middlecoff told a gathered crowd: “Hogan is a miracle man. I played a round with him several days ago. He pinned our ears back.”

Despite it being announced only three days prior that Hogan was playing, a record gallery of 9,000 poured into Riviera for the opening round. Hogan shot 73, plodding along with braces on his legs held in place by rubber stockings. The only time he looked healthy was when he swung. Valerie told reporters: “I was astonished, as well as happy, to find that he could finish the first round.”

If that was astonishing, what came next was impossible.

Hogan fired a second-round 69 to move into third place. In the third round, delayed by heavy rains, he followed with another 69, moving to within two strokes of the lead. More rains pushed the final round to Tuesday. Somehow, badly limping, Hogan shot yet another 69. He went to the locker room with a two-shot lead, thinking he was on the verge of victory.