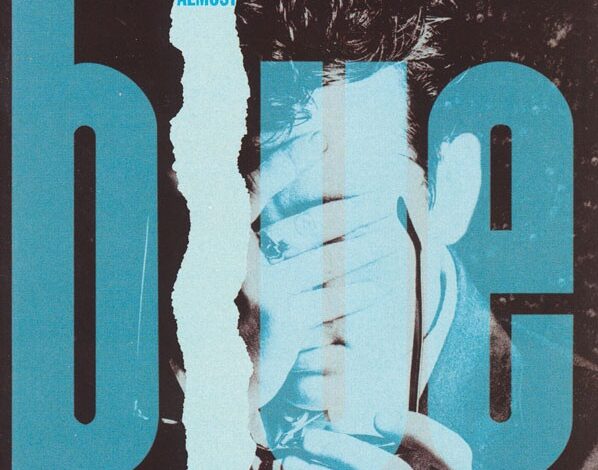

Elvis Costello’s ‘Almost Blue’ Was Rescued by Its Bonus Tracks… for a While

The release history of Elvis Costello’s Almost Blue provides a framework for examining how the delivery of recorded music can relate to our experience of it.

A Tear Through Audio Technology

In 1981, Elvis Costello released Almost Blue, an album of country music cover versions. In those days, the very early 1980s, LPs were released in three formats: vinyl records, cassette tapes, and eight-track cartridges, the last an audio technology some of you may never have experienced. Well, for that matter, some of you digital natives may never have experienced any of these technologies. At some point, you might have encountered a compact disc.

Almost Blue didn’t appear on CD until 1984, and at that point, only the original analog album had been digitized. Three years later, it emerged on CD in an expanded form that vastly improved on the original version and the original CD. The release history of this Elvis Costello recording provides a convenient framework for looking at how the format—physical or not—the delivery of recorded music can relate to our experience of music.

As for Almost Blue itself, We’ll get to it.

Getting There

You’d never know it from the current vinyl resurgence, but albums were supposed to be dead by now. People talk about collections of digital files as albums, but the term albums derives from LPs, long players, and 12-inch vinyl records consisting of songs spread over sides. Albums go back to when very early records, with just a couple or a few songs, were stored in physical folders called albums—like photo albums. You remember physical photo albums, right, with sleeves that stored prints of pictures? Photo albums now seem so 20th century, in good and bad ways. Over time, technologies fall by the wayside.

By the early 1990s, after ruling music retail for some 40 years, vinyl LPs were being phased out due to a lack of commercial interest. New recordings weren’t being released on vinyl. Even classic albums by major artists on major labels were becoming unavailable, seemingly never to be available again. Music fans who still owned turntables were out of luck unless they could find older records secondhand.

In those bygone days, many secondhand records in decent condition were being sold fairly cheaply. Today’s vinyl equivalent of tulipomania, with records of varying quality being grabbed greedily and prices rising accordingly, hadn’t begun.

At that time, CDs represented the state of the art of recorded music. Those little silver discs presented albus, buy weren’t albums as the form had existed for decades—as physical, analog discs that spun visibly and were read by needles. CDs functioned more or less invisibly, rendering music abstractly through the translation of ones and zeroes.

With the internet came tracks, freeing listeners even further from physicality and the tyranny of other people’s—artists’, producers’, and record companies’—assemblages. The future seemed to be tracks, with or without visuals, stored or streamed, shuffled and endlessly recombined. But that future took a detour when people discovered or rediscovered the pleasures of the album. Far from being discontinued, the album surged. In 2022, brick-and-mortar stores sell far more vinyl records than they do CDs.

Still, every format includes limitations. As vinyl neophytes have discovered and seasoned collectors have always known, the LP delivers its pleasures while foregrounding its limitations.

Almost There

To face one major limitation of the vinyl album, consider a record from predigital days: the Clash’s Sandinista!, released in 1980. The previous year, the Clash wowed partisans and newcomers with its two-record stylistic smorgasbord, London Calling. Their follow-up, Sandinista!, increased the sprawl, being a three-record set and even more unclassifiable.

The band intended the album to be sold at a discount, but—commerce containing its own laws—retail prices varied. Over the decades, Sandinista! always sold for a premium price. As an artwork and an artifact, the record remains highly valued.

In this collection, however, the Clash’s musical reach exceeded their grasp. Career highlights such as “The Magnificent Seven” and “Police on My Back” met career nadirs such as “Mensforth Hill”, which was an earlier song on the LP played backward, and the Clash’s early punk anthem “Career Opportunities” in a version sung by children. Let that sink in—it’ll relate to the Elvis Costello record when we get to it. Nearly four minutes of Sandinista! therefore, potentially, your listening life consists of another song played backward, and another two and a half minutes of a beloved “punk” song sung by children. Taking the good with the bad only goes so far, and by the time you reach side six of Sandinista!, you may want some of your money back.

With digital files, you can reorganize the tracks and skip some. By contrast, if you play the vinyl, you have little choice but to experience the whole pretty much as configured. Yes, you can play the sides out of order. You can lift your player’s tonearm and relocate it to a different part of the platter. But editing a record in this way takes work. Thus, the unique event of placing a vinyl LP on a turntable, lowering the stylus, and experiencing a sequence of sounds brings with it the potential for being trapped listening to things you dislike.

This brings us to the album Almost Blue.

There

It was 1981. The English musician born Declan McManus and dubbed Elvis Costello had, in the past four years, released five albums that placed him in the vanguard of smart, catchy pop-rock: My Aim Is True, This Year’s Model, Armed Forces, Get Happy!, and Trust.

Costello’s music had developed within a mid-to-late 1970s scene labeled pub rock. As that strictly English phenomenon faded out, some pub rockers became punk rockers, such as the Clash’s Joe Strummer. Some punk rockers became new wavers, such as Generation X’s Billy Idol. Like his fellow singer-songwriters Graham Parker and Joe Jackson, Costello never fully fits into any of these genres. He was too angry for pub rock, not angry enough (but too many other things) for punk rock, and too well-versed in traditional pop-rock for new wave.

His debut, My Aim Is True, proved an instant classic. It lacked only the stinging, supercharged, immaculate playing of his soon-to-be backing band, the Attractions. They consisted of keyboardist Steve Nieve, bassist Bruce Thomas, and drummer Pete Thomas. With the Attractions in place, starting with This Year’s Model, Costello seemingly could do no wrong. He was a top-notch songwriter whose wordsmithing matched his acerbic delivery and naturalness with melody. Album after album, Costello kept his balloon aloft, each time trying new things and mostly succeeding. His artistry was riding high—but his sales were descending since his music could not, would not, speak to the masses.

Then, in 1981, Elvis Costello tried an entirely new thing with Almost Blue: a record covering country songs. American country songs! Costello’s relationship with American music and culture had been vexed. On the internet, you can learn or refresh your memory about a notorious incident involving some American musicians, the US South, alcohol abuse, and Costello’s use of a particularly noxious racist slur. Here, suffice it to say that while Costello obviously loved the colonies’ contributions to popular music—including but not limited to R&B, soul, radio-friendly pop such as Motown, and the Great American Songbook—he bore an Englishman’s ironic distance from the roots of those forms. Despite his obvious commitment to his own songs and other peoples’, and despite, from the start, recordings of straight-to-the-heart sincerity (e.g., his own “Alison”, or his live recording of Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s “I Just Don’t Know What to Do with Myself”), he seemed too intelligent, sophisticated, cheeky, and self-aware to get down without putting a spin on his own moves.

Let’s jump ahead for context: In 1986, billed as the Costello Show featuring Elvis Costello, he released an album of what we’d now call American roots music, nearly all original. The title, King of America, carried so much baggage that it was hard to unpack, so listeners might have just chuckled at the general ideas and enjoyed the show. But they could do that—relax and not hunt for significance—because by then, Costello had begun separating himself from the Attractions and his role as an angry young songsmith. He had settled into a spot he still occupies: unpredictable, congenial, genre-hopping niche entertainer, sometimes operating under playful pseudonyms and the identity-switching implied by them.

In 1981, though, the idea of Almost Blue didn’t seem as amusing or entertaining as it was puzzling. If Costello wanted to cast (mostly) his own songs in a soul mode on Get Happy!!, his fan base went along for the ride. But who wanted to hear his take on country songs that didn’t necessarily need covering? What wrongheaded muse had signed off on this exercise?

Billy Sherrill, a Nashville music-biz fixture who had produced such superstars as Tammy Wynette, Charlie Rich, George Jones, and Barbara Mandrell, signed on to produce Costello’s country excursion. The Englishman must have wanted the American’s mark of authenticity. While Sherrill’s productions could be heavy-handed, Costello probably aimed for the spare, unpretentious touch Sherrill brought to, for example, Mandrell’s debut album, Treat Him Right (1971). Slot in Costello’s voice there, and you’d have a nifty album, a little bit country and a little bit rock and roll.

Opinions have always differed markedly on the results of Sherrill’s and Costello’s work together—or sort of together, sort of at a distance—and whether Costello’s personal problems, such as the end of his first marriage, infuse those results. On the internet you can learn or refresh your memory about the album’s critical and commercial receptions. For example, at the time, the self-proclaimed dean of rock critics, Robert Christgau, likened the album to David Bowie’s 1973 covers collection, Pinups, and John Lennon’s 1975 covers collection, Rock ‘N’ Roll. Christgau meant that when major artists devote their recording time to batches of other people’s songs, attention must be paid and, to some extent, will be rewarded.

Maybe at the time, Costello seemed to be developing the significance of Bowie, maybe (doubtfully) even of Lennon. How much attention his country covers ever deserved remains the big question. For the purposes of this article, suffice it to say that the self-proclaimed “bible of alternative rock”, Trouser Press, rightly called Almost Blue “a dud”. An emendation at trouserpress.com notes that “time has found the record a more organic place in Costello’s creative stream”—that is, the album has settled in its place and makes sense within Costello’s body of work. Although that evolution may be true, it doesn’t ameliorate Almost Blue’s unsatisfying listening experience. History is one thing, artistry another.

Some of the 12 tracks hold their heads up. Side one opens with a rambunctious tearing-into of Hank Williams’ “Why Don’t You Love Me”, this approach seeming like sacrilege until it settles into the irreverence that people probably expected Costello’s take on country to be. In those days, Costello was often labeled punk. His “Why Don’t You Love Me” sounds, improbably, like a punkish trashing by someone who doesn’t give a damn about country music or Hank Williams. The roughness of the recording suggests “the best we’ll get”. In concert, Bob Dylan might do this to a Dylan song. Something like it would fill space on the Clash’s Sandinista! more profitably than, say, “Mensforth Hill” (most anything would). As a way to pass some time, it beats, like Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start the Fire” (almost anything would). Still, one feels relief when it ends.

Billy Sherrill’s “Too Far Gone” is better, slower, and prettier, as is Jerry Chestnut’s “Good Year for the Roses”. The difference between these tracks and less successful ones may simply be that some of the performances give you a reason to listen. The album generally puts close listening to the test, defying attempts to figure out why and how the recordings work or don’t.

The closer, Gram Parsons’ “How Much I Lied”, works very well. Costello seems so comfortable and the accompaniment sports such a classic Attractions sound that this track would have fit comfortably on their next record, the 1982 pop-rock return to form Imperial Bedroom. That stylistically diverse album includes an original jazzy pop ballad, “Almost Blue”, which presumably gave the country-covers collection its title—and not vice versa.

For a sense of Almost Blue’s overall failure, consider the deadness of “Tonight the Bottle Let Me Down”. Of all the songs on the record, this Merle Haggard composition should have been easiest for Costello to inhabit. He was, after all, no stranger to the bottle. But his unengaged vocals and the awkward music never gel, instead suggesting people perform what they think country music sounds like.

“What were they thinking?” comes to mind during Lou Willie Turner’s “Honey Hush”, originally recorded by her husband, Big Joe Turner. Costello’s version is as forced a rendering of R&B as any white Englishmen ever attempted. Maybe Costello and the Attractions didn’t give it another try because the groove just wasn’t in them. Maybe Sherrill let this one go because it made no sense to him; their struggling at a song that wasn’t even country.

Such plasticky doings, odd decisions, strained vocals, and weak music, despite pianist Steve Nieve’s best efforts to juice things up and the occasional pedal steel of “special guest” John McFee, keep the record from ever taking off. Apart from curiosity or academic interest, why play such nonessential recordings when you could play more-pleasurable Costello or actual country music or something else entirely?

If you acquire the album on vinyl, whether vintage or reissued, you’ll likely want at least some of your money back. If, by contrast, you happen on one of the extended CD reissues, you’re likely to experience a revelation.

Which brings us to the beyond.

Beyond There

Rykodisc’s 2004 CD of Almost Blue appends 11 bonus tracks. These additions add up to a half-hour of music, doubling the original’s half-hour and utterly redeeming the original’s lifelessness. In his liner notes, Elvis Costello reveals that over 25 songs were recorded during the recording sessions, and the bonus tracks reveal that some of the best recordings didn’t make it onto the album.

The first five bonus tracks come from a 1981 concert and immediately improve the record. Costello soars and lands safely on Hank Cochran’s “He’s Got You”. Costello’s version holds its own against Patsy Cline’s version, “She’s Got You”. More importantly, this recording bests Costello’s take on a different Patsy Cline track: his cover of her signature song, the Don Gibson-written “Sweet Dreams”. That version appears on Almost Blue; its music and vocals feel stilted. By contrast, on the bonus track, “He’s Got You”, the players seem relaxed, and their lack of tautness gives the track atmosphere. Indeed, this live recording tops the entire original LP in its technique and feeling.

Elvis Costello’s version of Johnny Cash’s “Cry, Cry, Cry” has the rough edge of Almost Blue’s “Why Don’t You Love Me” without the tossed-off quality. Versions of two songs on Almost Blue—Charlie Rich’s “Sittin’ and Thinkin’” and Lou Willie Turner’s “Honey Hush”—redeem the originals with looseness and feeling. Hallelujah, Costello had a good “Honey Hush” in him after all.

Live in 1979, Costello & Co. sound on home turf doing Leon Payne’s “Psycho”, which asks the immortal rhetorical question “You think I’m psycho, don’t you, mama?” (Sure do.) Jack Ripley’s “Your Angel Steps Out of Heaven” from the studio during the sessions proves deeply soulful. The only failure in the bunch—an interesting, telling failure, if not a good listen—is an early version of Costello’s own “Tears Before Bedtime”, which would be arranged far more dramatically and appropriately on Imperial Bedroom. The quasi-country version of “Tears Before Bedtime” appears next to last on the Rykodisc collection, whose final track proves its best: “I’m Your Toy”, performed live in 1982 with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, makes the Almost Blue version sound like a run-through. Breathtakingly in the moment, Costello luxuriates in the song’s beauty and passion.

Rhino’s 2007 two-CD set adds yet another half-hour of material from the period, live and in the studio, and all these Ryko and Rhino bonus tracks make clear that Costello was in fine form at the time. He generally sounds like himself at his most inspired and not, as on the original album, like an escape artist publicly donning a straight jacket. He had beautifully rendered country music in him and on tape, but that music just didn’t happen to be released as Almost Blue. If you don’t like the original album but care about Costello’s take on country circa 1981, seek out the bonus tracks.

Here’s a complication related to ever-mutating music technology: In the 21st century, CDs are becoming increasingly scarce, and the original vinyl album now gets reissued sans bonuses. Maybe for Record Store Day, someone will create The Alternative Almost Blue, assembling the best bonus tracks into a—even the—country-covers record we might wish Costello had released.

Till then, let the non-diehard buyer beware. With Costello, the buyer must often beware. Past the (brilliant) Trust album—and the later rock-solid entries in his catalog, such as King of America—stylistic detours defy music collectors’ tendency toward completism. A fan of the taut, manic, even claustrophobic plastic soul of Get Happy!! might not appreciate the more relaxed, spacious, acoustic-based folk-pop-rock of King of America, but those works at least inhabit the same pop-rock universe. What’s the fan of either work to do with the string-quartet-backed epistolary renderings of The Juliet Letters (1993) or the orchestral work Il Sogno (2004)? “Not everything on it works equally well” could be shorthand for Costello’s oeuvre, whose highs and lows are generally acknowledged if not universally agreed on.

Bluish

Meanwhile, there’s a little something for everyone, diehards and newbies, on Costello’s covers collection from 1995, Kojak Variety. This assemblage feels like a spiritual twin to Almost Blue in any of its CD or vinyl incarnations, with or without bonus tracks. Not to overdo the critical reading into the situation or psychoanalyze the artist, but perhaps this second covers LP represents an attempt to recover ground. Consciously or unconsciously, Costello wanted to do covers on different grounds. He didn’t want to revisit Almost Blue but maybe wanted to make up for it.

In his liner notes for Kojak Variety, Costello mentions his coming later to country music than other genres due to the BBC’s playing mainly “novelty” country records he didn’t care about. He became “curious” about country only after hearing a country-rock album, the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968). Does Costello’s belated introduction explain the comparative ease of Almost Blue’s “How Much I Lied”, whose composer, Gram Parsons, was a guiding light of Sweetheart of the Rodeo? Did Costello’s disconnectedness from earlier sources, that something-once-removed background, contribute to the general stiltedness of Almost Blue?

In any case, having “recorded an entire album in Nashville”—that is, Almost Blue, which he doesn’t mention by name in these notes—Costello “wanted to do something different” with Bill Anderson’s “Must You Throw Dirt in My Face”. Thus, he transforms a country song initially recorded by the country pioneers, the Louvin Brothers, into an R&B ballad.

In addition to R&B, the genres on Kojak Variety include soul, radio-friendly pop such as Motown, and even the Great American Songbook. Country arrives sideways, through a version of Bob Dylan’s “I Threw It All Away”. The original appeared on Nashville Skyline (1969), Dylan’s excursion into full-fledged country. However, here it’s Attractions-style baroque pop played by such non-Attractions as guitarist Marc Ribot and drummer Jim Keltner. (On other tracks, Attractions drummer Pete Thomas appears, as do musicians who were billed as the Confederates on King of America.) Costello sings, and his accompanists swing dexterously. Textures shimmer. Highlights glimmer. By this time, Costello had fully absorbed the grit and the charms—the lessons—of country music, even when he wasn’t (playing at) playing it.

As a bonus, music collector: If you go digital with this collection, as with the Clash’s Sandinista!, you can improve the sequencing. Artistic vision or executive choices be damned. Some albums just beg for random play and the serendipitous discoveries of reshuffling.