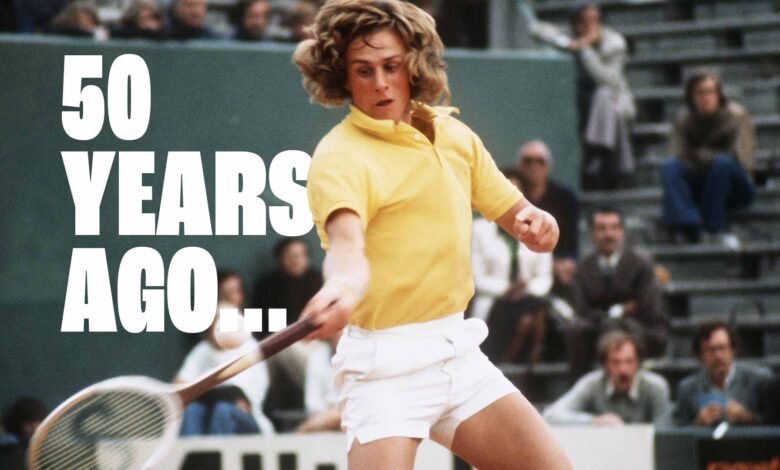

Bjorn Borg: 1974 Roland Garros Title, 50 Years On

With exclusive insight from Borg, his first coach and rivals, ATPTour.com recounts the Swede’s breakthrough run in Paris that triggered his rise to sporting icon. The depth of his groundstrokes was striking; his court speed and ability to play big points so well, was on another level, while his first-serve percentage under pressure was amazing. Those on the international circuit in the infancy of Open Tennis, knew Björn Borg was coming. For many, they foresaw the break-up of traditional serve-volley tennis with a new level of physicality, intelligence, and consistency in the precocious 15-year-old, fresh out of school.

There had been baseliners before, but instead of yielding to critics of his technique, the Swede was able to absorb punishment in matches and showcase resilience time and again by focusing solely on the next shot. For it’s all Borg had known since first striking a ball against his garage wall on Torekällgatan 30 in Södertälje. He didn’t receive any coaching for the first three years. “Upon leaving school, I gave myself two or three years before I’d potentially return to my studies,” says Borg, 50 years on. He never needed to look back.

“I took training just as seriously as matches from a young age, and that was one of the keys to my breakthrough and career,” Borg told ATPTour.com, from his home in Stockholm. “My mentality was one of my greatest strengths and I went onto court training myself to focus.

“I learned to concentrate initially for an hour, then two hours, and early on the pro circuit, I knew I could last however long the match lasted. In training, I would empty my mind and think only of the present: the next ball, the next shot. I’d focus on switching on and off, of winning the next point. ‘I have to win. I have to get the impossible ball back.’”

Percy Rosberg immediately recognised a special talent, when he first met an 11-year-old Borg in 1967. Today, the 91-year-old still takes the three-minute walk from his apartment to SALK Hall, his second home.

“A boy got sick, so Björn jumped into a group of 10 talented children,” said Rosberg, who had once been the Swedish No. 4 behind the likes of Sven Davidson, Uffe Schmidt and Jan-Erik Lundqvist. “In our first hit, Björn moved me around the court for 20 minutes, getting every ball back and moving me from corner to corner. His footwork was fantastic. I tried to put him in his place, correcting his backhand technique, but it didn’t work. He had total control over length of shot. I felt, even then, Björn already knew that if he put the ball over the net one more time than his opponent he would win. Anyone can have good strokes, but if a player has a good head they will do well in the pressure of matches.”

For Borg’s achievements were already considerable prior to the start of the 1974 French Open at Roland Garros. Former World No. 3 Tom Okker, who now lives six months of the year in South Africa, remembers, “We all saw his potential. His game style, even then, was the same, centred on fitness, strength and speed around the court.”

In a legal sense, Borg was a boy when he became the youngest Italian Open champion in late May 1974, but as he flew down after practice from Stockholm to Paris, only a matter of hours before his first-round match against France’s Jean-Francois Caujolle, at 4 p.m. on Monday, Borg’s mentality and approach to fitness training was already set in stone. Lennart Bergelin, who’d become like a “second father”, and Rosberg, who had developed Borg’s distinctive topspin groundstrokes, had seen to that. Of Bergelin and their focus, Borg says, “We took one match at a time. ‘You’re playing this match, now it’s the next guy.’ We never looked ahead. He knew I was in good shape; he could tell looking at my face if I was ready. He would tell me who I’d play, and then we’d prepare.”

Speaking 50 years on, Rosberg, still smiles at the memory of Borg’s second appearance at Roland Garros, following a fourth-round exit in 1973. “Björn and I practised together on the Friday and Saturday, then I said, ‘Now, you should get ready to go to Paris and you’ll play your first match on Monday afternoon.’ Bjorn said, ‘No. I want to practise with you, here, on Sunday. I don’t have anyone to practise with. I practise with you on Sunday.’ So we trained together in Stockholm the day before his first match in Paris. It was stupid! Who, among today’s players would arrive only a matter of hours before their first match?”

Borg carried the same game he first showcased to Rosberg to the very top. “He had a two-handed backhand, but he tried to hit his forehand more than his backhand,” says Rosberg of 11-year-old Borg. “I could understand that, as he did not move as well to his backhand side. When he came to me, I taught him really how to dance and how to step for his backhands. He was the hardest, most dedicated student I met. As a 15-year-old, on his Davis Cup debut for Sweden, he adopted the same tactics: get the ball back, have his opponent hit one more ball and use his footwork to excel.”

Having had breakfast at Arlanda Airport in Stockholm, Borg, Bergelin and Rosberg landed in Paris and went straight to Roland Garros in the city’s south-west corner. That first evening, Borg dug himself out of a hole at 1-4 down in the deciding set against Caujolle, coming within two points of an early exit, and over the next 12 days the third seed negotiated victories over the likes of American Erik Van Dillen, ninth seed Raul Ramirez of Mexico and, another American, Harold Solomon. “I didn’t mind playing five-setters,” said Borg. “Even before my first Grand Slam win, I felt as if I was very strong mentally. Five sets never bothered me. I never got tired on a tennis court, I still felt fresh physically and mentally. Youth was on my side, and I won those important points.

By 16 June, as Borg’s wooden racquet landed on Parisian terre battue, everything changed with a swarm of on-court autograph hunters and photographers. Before he wore his headband; grew a wispy beard; had an airline fly 40 newly strung racquets (35kg/77lbs) from his favourite stringer in Stockholm to all over the world; wore fitted clothing and observed myriad daily rituals that all became a part of his iconic mystic, Borg was a major champion. Aged 18 years and 10 days. The superstitions, such as “rushing out to my preferred chair on the court” came when he returned to a tournament in a bid to retain a title.

There was personal disbelief as Borg found his court-side chair, following a 2-6, 6-7(4), 6-0, 6-1, 6-1 victory over Spaniard Manuel Orantes, arguably the world’s best clay-courter. “I arrived with a lot of confidence, but Borg was a phenomenon and had progressed very quickly,” admits Orantes, 50 years on. Borg maintained a sheepish smile as he scanned the 18,000-strong crowd to catch sight of Bergelin, who’d been without Rosberg’s coaching support since the quarter-finals. The pre-match feeling was that Borg was meant to be “a player for the future. Not today…” remembers Stan Smith.

“Going into the final, I felt I was going in as favourite,” says Borg. “I felt I had a good chance, but for me to play in my first Grand Slam final was a big thing. It was Orantes’ too. He had more pressure, because of his age. Even though I lost the first two sets, I still felt I had a good chance to win. After the tie-break, I still thought I had a chance.”

Former World No. 3 Brian Gottfried, who finished runner-up to Guillermo Vilas in the 1977 Roland Garros final, told ATPTour.com, “Once Borg arrived, he showed that there was more than one way to play tennis.”

The American is well placed to assess Borg’s development, having squared off against the Swede on 11 occasions between 1974 and 1980. “When Björn was playing well the depth of his groundstrokes was striking, I felt he wouldn’t let me in. When his groundstrokes were shorter, I knew that I was able to play my own game. His serve improved dramatically as the decade went on. His first-serve percentage under pressure was amazing. He had a tremendous ability to play under pressure, his style of play was different – high percentage tennis with his topspin groundstrokes. His court coverage and speed were incredible. It was in complete contrast to others who played offensively, more aggressively with flatter groundstrokes. He didn’t appear to have a nerve in his body.”

Looking back, Borg admits, “Winning the Italian Open gave me a load of confidence. I was not the favourite to win [in Paris], but I had a good chance to go very far. To win the whole thing, I never really believed it myself and I don’t think people believed it anyway. I played a lot of close matches in the tournament, and won, but I was strong throughout.

“You work all your life. You start with a sport you love, you set your sights on a lot of things, you have goals and dreams, you sacrifice a lot and finally you win that last point of a Grand Slam tournament. Not many players win a Grand Slam tournament, let alone just after your 18th birthday. It’s the most beautiful feeling.”

Orantes had beaten Arthur Ashe and Vilas en route to the title match. The Spaniard played some glorious tennis in the final and led Borg 4-1 in the second set, before his movement became impaired due to a back injury. “I trusted myself, but at the key moments my playing level and energy dropped,” Orantes, who continues to live in Barcelona, recalls. I couldn’t control the game and keep going. He won with much superior form.”

It was a lesson for Orantes, who went onto win the 1975 US Open and 1976 Masters [now named Nitto ATP Finals] in Houston. “At the end of the year, I was worried and looked for a doctor in Barcelona to help me,” says Orantes. “I worked a lot building up my muscles and that made the next two years the best of my career. When I first saw Borg, I realised that the way of playing would change, and the matches would be more physical, similar to [Rafael] Nadal.”

In contrast, Orantes’ countryman, Rafael Nadal, now coming towards the end of his all-time great playing career, earned the first of his record 14 trophies at Roland Garros in 2005, aged 19 years and two days. To date, only Mats Wilander, aged 17 years and 288 days in 1982, and Michael Chang, aged 17 years and 109 days in 1989, have lifted the Coupe des Mousquetaires at a younger age than Borg.

For it wasn’t just Borg-mania and hundreds of hysterical schoolgirls who had surrounded the shaggy-haired and lithe Swede and a team of policeman to get him from the dressing room to the court on his Wimbledon debut in 1973, which heralded the sport’s next superstar. But it was his consistency and exploits in 1974 — winning eight titles from 14 finals — that provided established stars with definitive proof of a player for the professional era.

Stan Smith beat 17-year-old Borg the first time they met in the 1973 Båstad semi-finals, under the gaze of Gustav VI Adolf, King of Sweden. Smith remembers, “He made too many mistakes in that first match, going for big shots, but you could see his tremendous fitness levels. The next year he’d become a ‘human ball machine’, realising that he didn’t need to go for big shots and that his speed around the court would make him difficult to beat. He was so fast that if he could just get to the ball, he wouldn’t lose. He came to the French and everyone was saying he was going to be a terrific player in the future, when he gets older. But 1974 was his coming out party.”

Early on, John Newcombe had noted how Borg’s unnatural groundstroke style — the high take back and follow through on his forehand, and the technique of his double-handed backhand — may soon wear down his wrist and shoulders. Today, Smith acknowledges that the Swede’s “service speed, the weight off his forehand and backhand slice approach shot were developments” to his armoury deeper into the 1970s.

During the 1974 Roland Garros trophy presentation, Bergelin stood beside Borg and explained to the crowd, “I was really nervous, and I have never been so nervous in my life. I think it’s more difficult watching the match than being on the court.” The 1948 French doubles champion with Jaroslav Drobny, ensured that all the mistakes he’d made as a player would not filter into Borg’s pursuit of becoming the leading tennis star. Rosberg, who went on to coach Stefan Edberg between the ages of 16 to 18, switching his double-handed backhand to a single-hander, recalls, “We learned from our mistakes and looked back on our own playing careers. Lennart and I were able to inform Björn to change things to improve. Björn understood that and knew we wanted the best for him. We all had a very good relationship.”

Rosberg, who’d left Bergelin after Borg’s five-set fourth-round win over Van Dillen, had watched Borg’s milestone moment with his wife, Majvor, in Båstad, a summer resort and home to the Swedish Open each July. Rosberg had a contract there for 32 years and needed to open a shop.

The architect of Borg’s dominance was Bergelin: a full-time coach for the modern age, a confidante and companion, who left his charge to relentlessly push through to 16 Grand Slam finals in 28 major tournaments. Regardless of the opponent, Bergelin would challenge Borg to leave nothing to chance. “Even if we have to lie, to suppose this opponent will be really tough, or this condition will make it really tough, that is how we think before a match,” admitted Bergelin. “One way to say it is that even if a threat is not there, we see a threat.”

“Lennart wasn’t just my coach, we were so close,” says Borg. “He knew everything about tennis. The most important thing was that he had contacts all over the world, because he had been ranked in the Top 10 as a player in the 1950s. So he knew everyone to contact, whether I needed to practice or he’d do something if I got injured and needed a physio.

“I could go out to a tennis court and wouldn’t miss too many points or balls. Tactically, we discussed about mixing up my game; to be aggressive at times and come in, because the other players didn’t know what you might do. But never too much. The players knew that if I stayed back, I was very tough to play and beat. I needed to switch up the tactics a few times and play mind games so to throw the opponent out of rhythm.”

Borg focused on tennis, nurturing his highly individual game, “a triumph of natural ability over orthodoxy” as long-time BBC broadcaster John Barrett once wrote, to win 11 Grand Slam singles crowns — a further five at Roland Garros (1975, 1978-81), and five straight at Wimbledon (1976-1980).

“We celebrated titles, but Lennart quickly put the focus on the next tournament that I was going to play,” says Borg. “Winning was more important for me and Lennart. That was the most important thing in life. My fitness and mental side remained the same throughout my career. I improved my serve, my confidence in going to the net, and I was a little more aggressive with my groundstrokes. From 1974 to 1980-81, I knew if a player were to beat me, particularly on clay courts, they would need to play their best tennis. Clay was always my preference.”

Bergelin passed away in 2008. “We never got upset with each other,” says Borg about their partnership. “He knew me, and I knew him. Sometimes he played a game with me to put me in a good mood. He wanted me to get into a good mood, to feel good mentally and physically. He could look at me and took time to get me in the best mental, psychological mood. He took me to the highest level and sometimes I didn’t realise that. If I lost, we were both so p***** off that we’d talk about it, but Lennart was even more upset than me!”

Rosberg, who worked as Borg’s coach from ages 11 to 19, continued to hit with Borg in the build-up to tournaments throughout the 1970s. He went on to coach the likes of Edberg, Peter Lundgren, Magnus Norman and Joachim Johansson and today oversees a group of talented 18-20-year-old Swedes at SALK Hall. Aged 91, he remains rightly proud.

“Björn didn’t have any great shots and he simply put his serve into court as a 17-18-year-old,” says Rosberg. “But he didn’t make many errors and continually got the ball back. His groundstrokes steadily improved, he became more aggressive and adept at coming to the net. I knew when Björn was 15-16 that the kind of game he played, getting the ball back and running from the baseline, may not have been stylish, like Roger Federer’s game, but I could not believe that he went onto win so many Wimbledon and French titles. It was great and I am so proud of him.”

In June 1974, having become the youngest champion (at the time) at Roland Garros, Borg was crystal clear about the future. “Even when I won my first French Open title, in my first Grand Slam final,” remembers Borg, “I said to myself ‘I’m going to win more Grand Slams. I want this. I know I can be a better tennis player’. I felt by winning my first at 18, I knew I’d win more in the future.”

At the Centre of becoming a sporting icon, Borg always had tremendous support from his parents, Rune and Margaretha, who visited Grand Slam tournaments in London, Paris and New York, every second year. “They were very important to be there for me,” says Borg, now aged 68. “To see them watching in the stands was more important to me than the pressure of winning. My parents were understanding, supportive of me, recognizing as and when, in my teenage years, I was becoming too involved — perhaps by not making me practice in the early years. They were the safeguard. They wanted me to enjoy the sport, helping and advising but never imposing restrictions. I had very good parents and without them, I don’t believe I would have had they success I did.”

Only Nadal (2008 and 2010), Roger Federer (2009) and Novak Djokovic (2021) have since clinched the Roland Garros and Wimbledon men’s singles titles in the same year. The ‘Ice Man’ achieved it in three consecutive years, 1978-79-80.