Marvin Leonard, Ben Hogan, and Their Legacy Friendship

The greatest legacy Marvin Leonard and Ben Hogan left behind was friendship.

The Charles Schwab Challenge at Colonial Country Club plays its 76th tournament later this month on Marvin Leonard’s fabled links along the Trinity River, a layout best known by its more common alias, “Hogan’s Alley.”

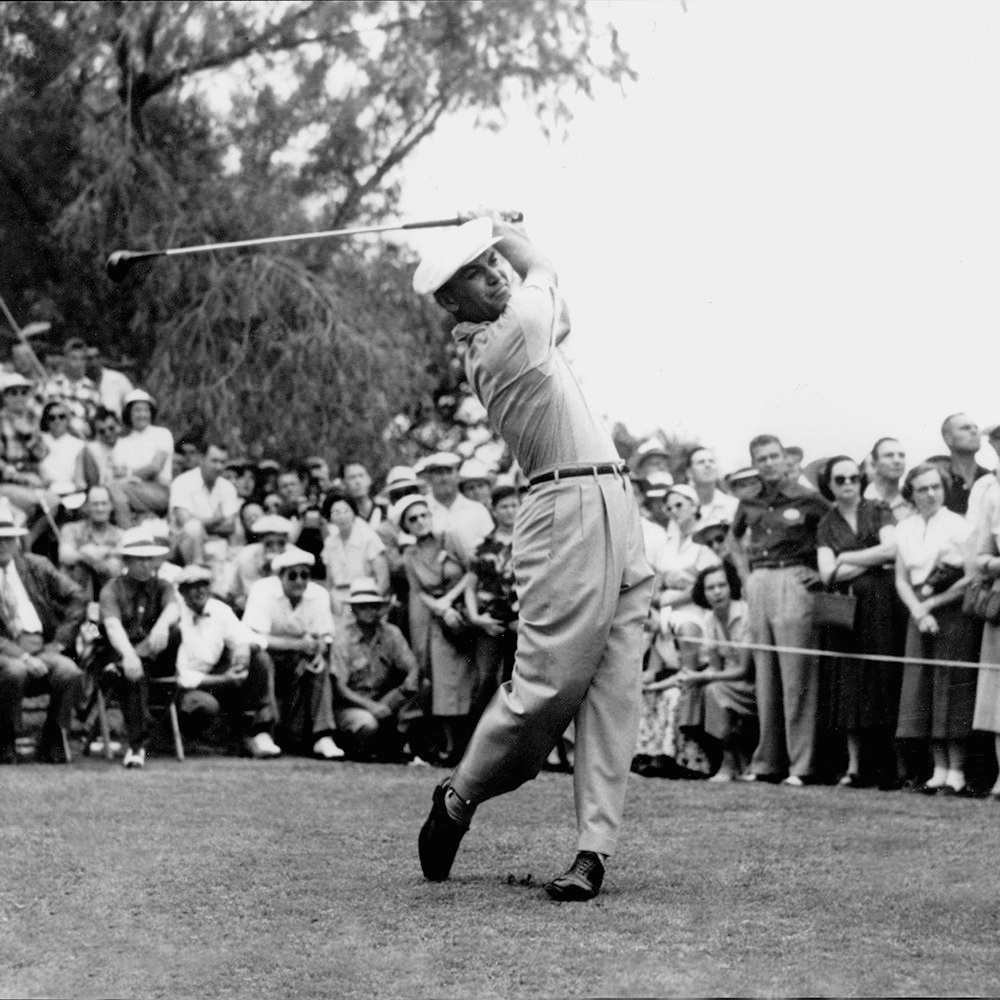

Ben Hogan, one of Fort Worth’s most distinguished citizens, won five times at Colonial, more than anyone else has ever dreamed of. To commemorate his dominance there, as well as his association with the place, a statue of Hogan overlooks the 18th green with notes of his feats adorning the base.

The story of Hogan, nine times a golf majors’ winner, is the story of possibilities and imagination. Of hopes and dreams achieved. And of dogged perseverance and grit.

Use of the term “American hero” for him is not mere embellishment or fancy embroidery on words. Who else except American heroes receive ticker-tape parades in New York City? Hogan, coming back from near death in 1949, took his place among the greats by being feted in 1953 with New York’s high honor, joining the likes of Teddy Roosevelt, Pershing, Lindberg, Ike, Truman, Nimitz, Churchill, and MacArthur. A pianist from Fort Worth would also receive the honor in 1958.

One can say with little reservation that it probably doesn’t happen without Fort Worth, the place that molded this resolved taskmaster, who as a young boy walked six miles to his job as a caddy at Glen Garden Country Club and often slept there so as to ensure he got the earliest tee times and the best tippers. As a caddy, Hogan was smart and “learned to get professional people who would tip him well,” his mother recalled years later.

And Hogan’s story of renown also probably isn’t written without Marvin Leonard, the town’s leading citizen in his day and, according to one description, its “voice of reason, compassion, and optimism.” And, of course, the city’s leading promoter and benefactor of the sport of golf, which he revolutionized in Texas with the introduction of the bent grass greens everyone told him he couldn’t grow in North Texas because of the heat. He put them on the championship-caliber course he built near TCU which hosted the 1941 U.S. Open and an annual PGA Tour stop beginning in 1946. The other club he built, Shady Oaks, had them, too.

There’s a common theme among the greats among us: They’re the ones who do things the smartest people in the room say are not possible. That was certainly one thing these two friends — these two greats — had in common. Much has been written on the topic of friendship, since before and including the Greeks’ great thinkers to singers and songwriters to script writers at NBC and elsewhere. It’s the relationships that matter, friends being the essential ingredient to making good in this world — no matter how that is defined — and for Hogan, Leonard was that friend, who stood by him and helped him get his career and perhaps even his life off the ground.

“The best way I can describe [the relationship] is the inscription Hogan wrote to my father in his first instruction book,” says Marty Leonard, daughter of Leonard. “‘To Marvin Leonard, the best friend I will ever have. If my father had lived, I would have wanted him to be just like you.’” “That tells you as much as anything. That was certainly the way Hogan felt, and I know my father felt the same way as well.”

True friends are a sure refuge, Aristotle said from his lectern at the Lyceum, it is presumed, in poverty and other misfortunes in life. Hogan needed refuge in his early days. One reason he was so poor was because he came from a dysfunctional family broken up ultimately by his father’s suicide. Many believe Hogan, then 9, witnessed his father’s suicide, but it was more than likely his 12-year-old brother, Royal, who entered the room.

“Daddy, what are you going to do?” asked Royal, according to news reports of the incident in the 300 block of Hemphill Street at about 6:30 p.m. on a Monday in 1922. Chester Hogan jerked a gun from the bag and shot himself just over the heart.

To those in the prime of life, friends “incite to noble deeds.”

The name Leonard and the department store he and brother Obie owned and operated for the better part of 70 years cannot be separated from the history of Fort Worth.

One reason is because Leonard was incited to noble deeds.

One example was retold in a Leonard biography, Texas Merchant, authored by Walter L. Buenger and Victoria L. Buenger.

A program to feed hungry school children during the Depression, financed by the state and county budgets, had run out of money. Leonard told the schools superintendent to keep the program going and send him the bill. He quietly paid the $35,000 bill to do so. He wasn’t the kind of guy to go on Facebook — had there been a Facebook — and tell the world what he had done.

He didn’t operate that way. Leonard was a “quiet giver,” his daughter once said, adding in one testimonial that he was always “helping people in some way, whether it happened to be with paying bills, or with food programs at local schools, providing college funds, or helping out in a personal crisis. Everybody loved him, and that was because Daddy loved people.”

This was a guy who didn’t finish high school because, as his brother Obie said, as retold in Texas Merchant, he didn’t want to burden his parents with the expense of buying him a graduation suit.

Leonard’s Department Store was also the first in Fort Worth to remove the last ugly vestiges of Jim Crow, according to Texas Merchant. The store had always welcomed Black shoppers, but it had separate water fountains and bathrooms. Blacks were also not allowed in the buffet line of the store’s restaurant.

It was an example that is credited for making way for the one of the most peaceful transitions of desegregation in South.

Of his quiet philanthropic pursuits, Leonard would say later in his life that, “Whatever I might have contributed to the field of golf and to the welfare of my city, I received deep personal satisfaction — more than I know how to express.”

As it concerns golf, Leonard initially put the game away as quickly as he had picked it up. He tried to play in his early 20s but found the game took too long to play. He reasoned that even as a bachelor, he was too busy with an upstart business in downtown Fort Worth to mess with chasing a white ball around a golf course.

A doctor convinced him to change his mind some years later when Leonard was in his early 30s.

“I woke up one morning feeling so low that I went to my family doctor, and he said to start playing golf or start preparing for a crack up,” Leonard said, according to Texas Merchant.

He returned to Glen Garden and began playing at least nine holes in the morning before breakfast. His hobby turned to obsession, as we all know the story of his proving that bent grass greens could not only survive but thrive in Texas. He had discovered them in California.

It was at Glen Garden that Leonard met the hardscrabble Hogan, then a teen, the pockmarks of the disease of poverty covering him from head to toe.

Leonard befriended him, and it’s not a stretch to suggest that the older man — 17 years older than his new protégé — was the only true friend at that time of Hogan, who left Glen Garden in a fit of rage, never to return, believing he had been cheated out of winning Glen Garden’s caddy tournament by members who liked Bryon Nelson more than him. According to Hogan, he had beaten Nelson in a nine-hole playoff only to lose when members extended the playoff to 18 holes to give Nelson a chance. Nelson won and with his victory received a junior club membership.

The experience was a seminal event in the life of Hogan, who, author Dan Jenkins once told me, remained hurt by the incident up until his final breath.

In those early days on tour in 1931, Leonard seeded Hogan’s first year. By Christmas, he was out of cash and stuck on the West Coast with no way to get home. He called Leonard for another advance. Leonard wired him money, with enough to buy his fiancé a Christmas gift.

Marty Leonard said she doesn’t know how much money her father gave to Hogan, other than the crude, simple one-page document kept in the Hogan Room at Colonial. It’s a matter of a few hundred dollars (roughly $5,000 today).

“I’m sure there were other instances,” she said. “That’s the one we have record of.”

Hogan’s first 10 years as a professional were difficult. His first victory didn’t come until 1940 at the North and South Open in Pinehurst, North Carolina. From 1945-49, Hogan won 37 tournaments, including the PGA and U.S. Open twice.

The accident in Van Horn almost ended it all. Hogan cheated death twice from the collision with the bus. He suffered a broken left ankle, a fractured collarbone, multiple fractures in the pelvis, and a damaged rib when his car, which also carried his wife, Valerie, as a passenger. In the aftermath of surgery to repair his injuries, he also developed what was described as a serious blood clot condition that compromised his life.

Leonard didn’t fly out to El Paso, Marty said, but he was intimately involved.

“I can remember as a youngster waking up in the middle of the night hearing my father on the phone,” said Marty Leonard. “Daddy had some connections with at Carswell [Air Force Base]. They were trying to fly Dr. Ochsner, who was in New Orleans, to operate on Hogan.”

Alton Ochsner, a professor of surgery at Tulane University who had flown to El Paso on an Army airplane, called the surgery a “complete success.” The doctor said he had made an incision in Hogan’s abdomen and tied off the vein from where the clots had appeared.

It was similar, the doctor said, to “turning off a water faucet.”

“We removed the danger of any more clots,” he told reporters then, “and another one could have been fatal.”

He predicted that Hogan would be “up and around in a few months.”

History tells us how this remarkable story ended. In June of 1950, 17 months after the accident, Hogan, then in his mid-30s, won the U.S. Open at Merion Golf Club, and he went on to win six more majors.

In 1951, Hogan won his first Masters tournament and in 1953 won the Masters, U.S. Open, and British Open. He might have won the PGA had he played in it, but that tournament conflicted with the British Open (if you can believe that).

The ticker-tape parade in New York followed, a celebration ultimately of the American spirit and overcoming his accident and his empty pockets.

“Hogan’s comeback was just amazing,” said Marty Leonard, who recalled following Hogan around the Colonial tournament “like a puppy dog.”

“That he could ever walk again and play as he did was amazing.”

Hogan’s last victory on tour was the 1959 Colonial. He defeated Fred Hawkins by four strokes in an 18-hole playoff. One observer was Marty Leonard, who skipped classes at SMU that Monday to watch.

The friendship between Leonard and Hogan remained steadfast until the end of each other’s lives, said Marty Leonard, who noted also that her father was an investor in the Hogan Co., a manufacturer of golf clubs.

“He threw out the first set of them because he didn’t like them,” she said. “I think he lost some of his investors when he did that, but not my father.”

Colonial members held a roast of Leonard in 1969, which turned out to be the final year of his life.

Hogan was the star attraction.

“For the edification of you out-of-towners, we here in Fort Worth like to honor people who have never made a success of anything,” Hogan said dryly. “We pick out people who have never contributed one thing to this city’s success. We only honor complete parasites.”

After pausing, he added: “Our honoree tonight goes beyond that.”

Hogan joked that Leonard’s career had been a series of “mistakes,” which his brother Obie had to bail him out, including coming to the rescue of Leonard’s Department Store after discovering Marvin was “giving away” the merchandise. “While Marvin was home sleeping, Obie was down at the store changing prices.”

Hogan then grew serious and said: “Marvin Leonard has done more for golf with his time and his knowledge and his money than anyone I know. I don’t know that anyone else would have the nerve and foresight to do the things he did. I doubt if Colonial would exist. I doubt if Shady Oaks would exist. I doubt if the U.S. Open would have come here. Marvin, I salute you.”

There also might not have been the Ben Hogan we know.

In the years that followed Hogan’s success, the golfer offered to pay back the money Leonard had given him, Marty Leonard said.

“Ben,” Marvin Leonard said, “you don’t owe me anything.”